How I Ruined a $55 End Mill (Embracing Failure)

Failure isn't fun. We all have a desire for success and when an endeavor goes poorly we aren't having a great time. In truth, failing and learning is a huge part of the engineering process (much of science and engineering consists of smart people failing and making terrible guesses and improving as they learn). I hope that my journal of this particular failure helps you not make the exact same mistake and provides comfort that failure is a very normal part of the creative process.

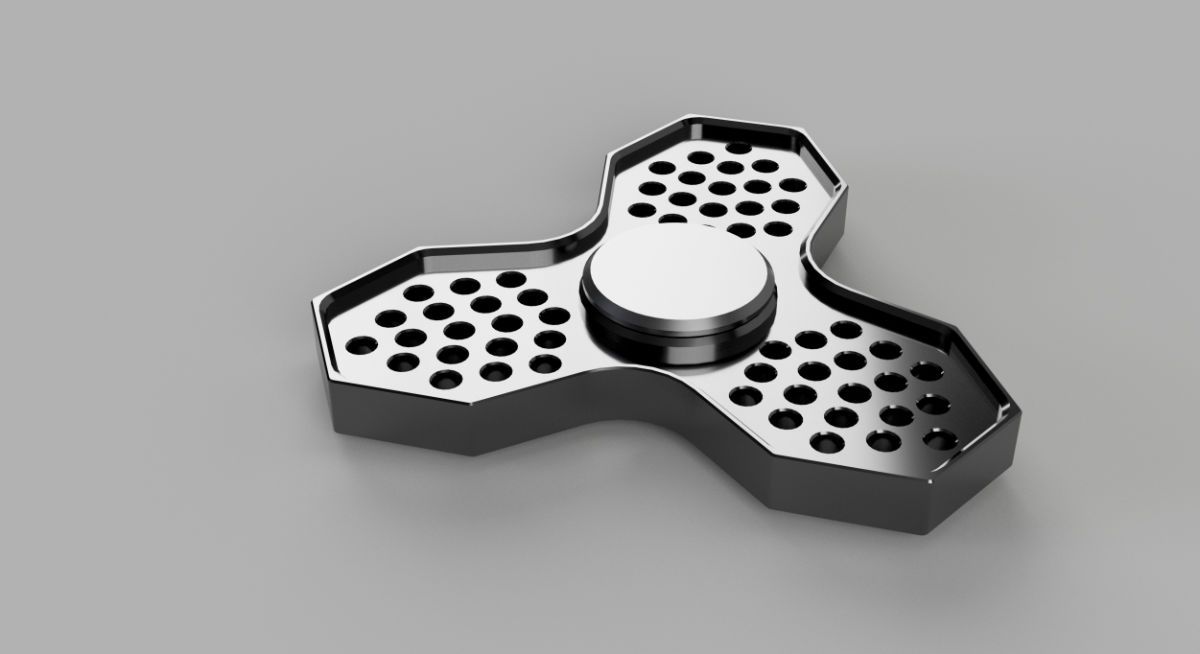

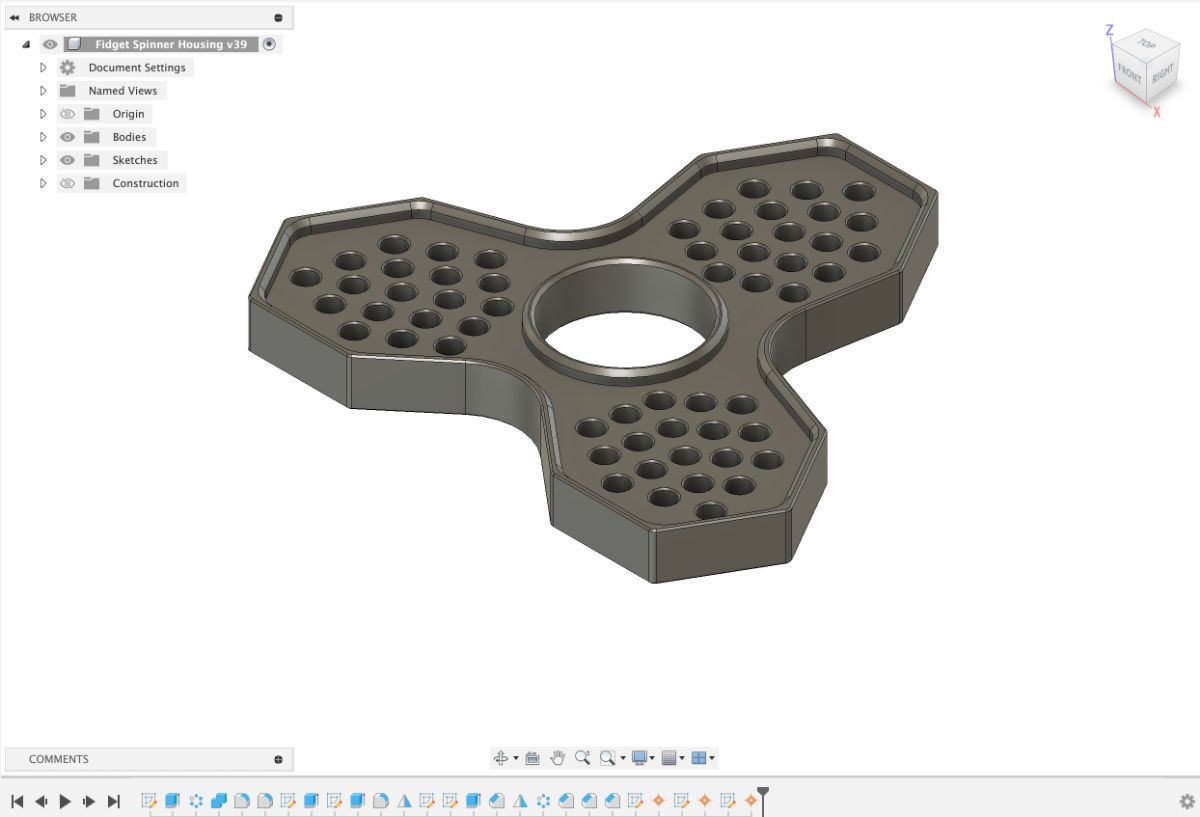

My planned project this weekend was to machine a fidget spinner from a large block of remnant aluminum. It was designed to intentionally exercise the capabilities of a 3-Axis CNC machine with multiple sides and tool changes while being easy to setup in a vise.

The main body of the spinner shown in figure 2, requires several operations on both the top and bottom side. The body is symmetric on the top and the bottom.

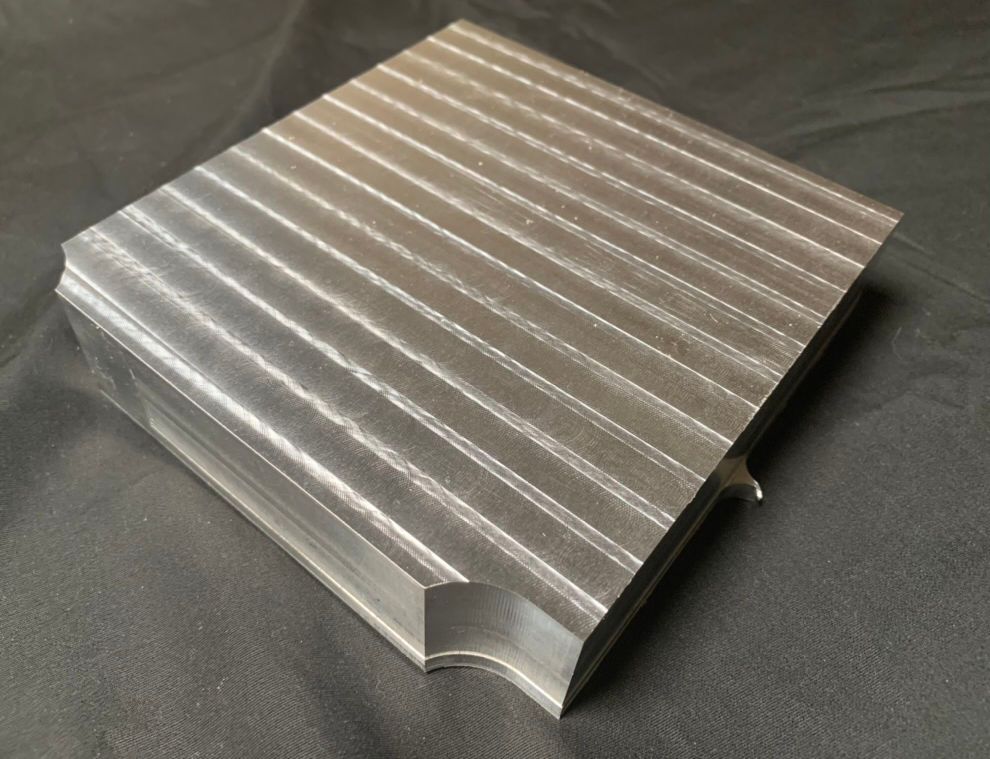

The raw stock for the spinner was an aluminum remnant from a local machine shop that was going to scrap it (about 5"x5"x1.25" in size).

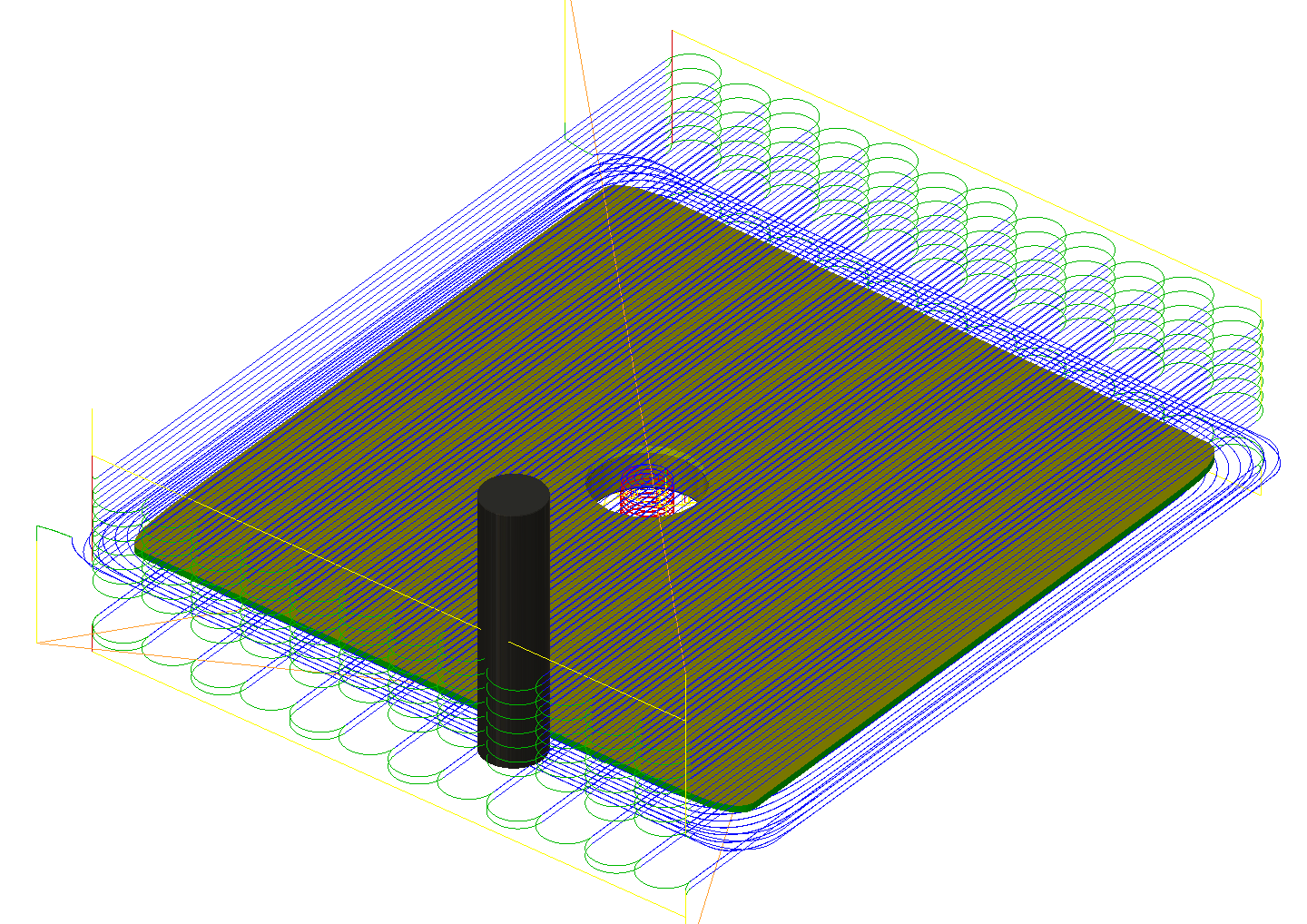

I have a 3-Axis CNC mill without an auto-tool changer so it's important to keep the number of tool changes and setups reasonable, especially for a one off part like this. The plan was to make the spinner main housing using a 1/2" End Mill, a 1/8" end mill, and a 1/4" 45 degree chamfer mill. The planned tool paths are shown in figures 4 and 5.

Pay very close attention to side 2. During this side, the fidget spinner housing is clamped into the vise while the rest of the stock is cantilevered outward. The tool plan removes material from the entire block until the whole block is relatively thin, about 1.5mm. The tool then removes the remainder of the material.

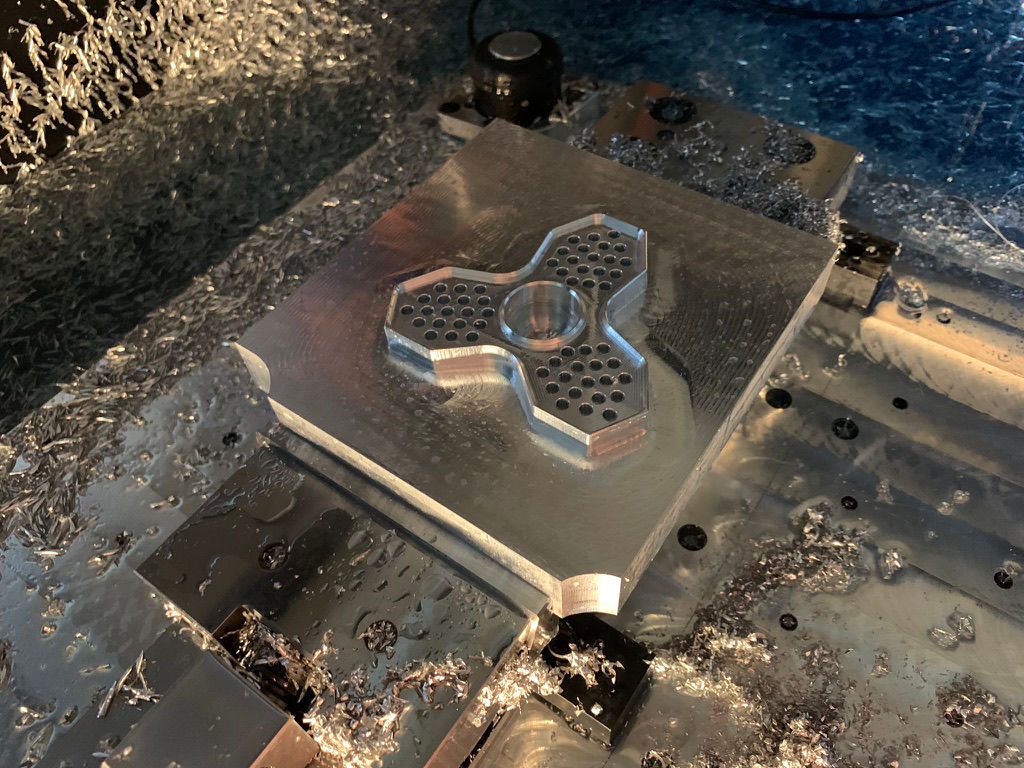

Side 1 actually went REALLY well and without issue, as shown in figure 6.

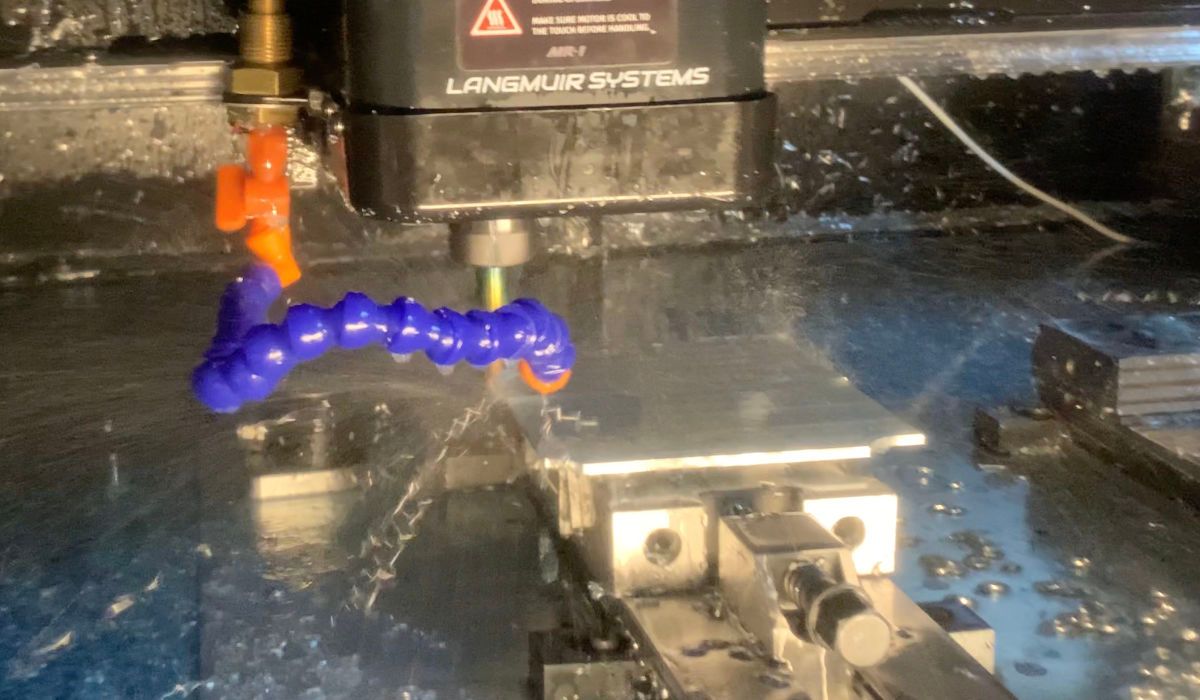

The 2nd side appeard to be going just as well until a a ringing vibrational noise could be heard whenever the cutter move to the corners of the remaining stock on the part; the vibration became worse with each layer until at last the final layer had been reached. During this last layer, the vibration was extremely audible and coolant could be seen bouncing nearly an inch off the surface of the part.

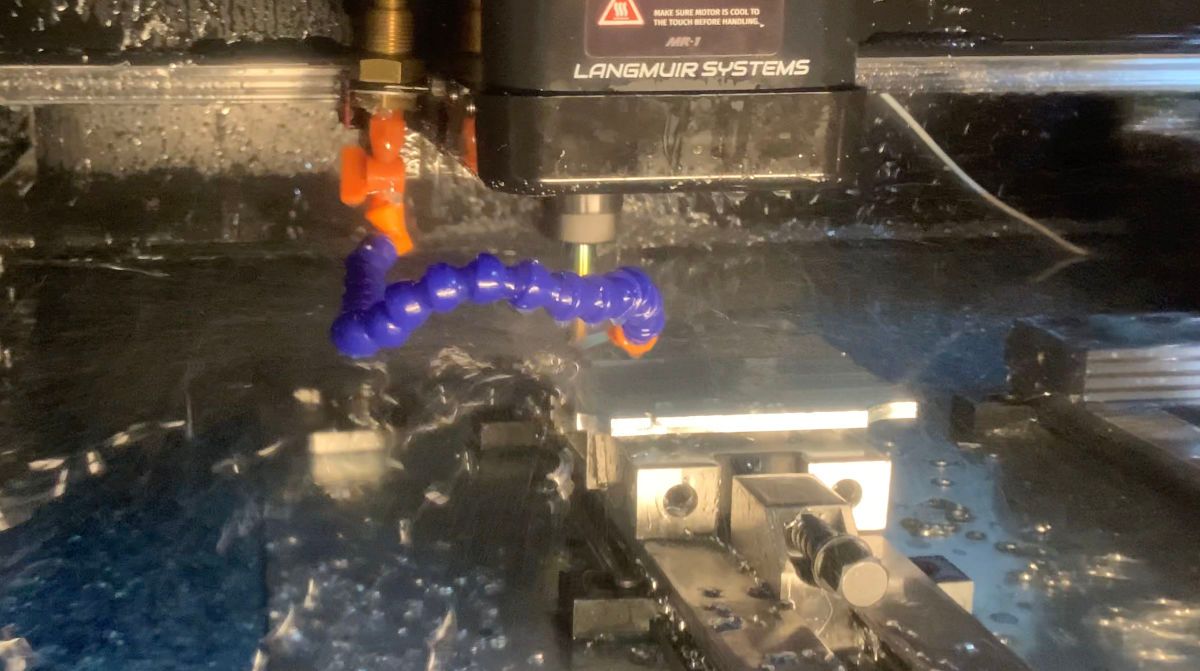

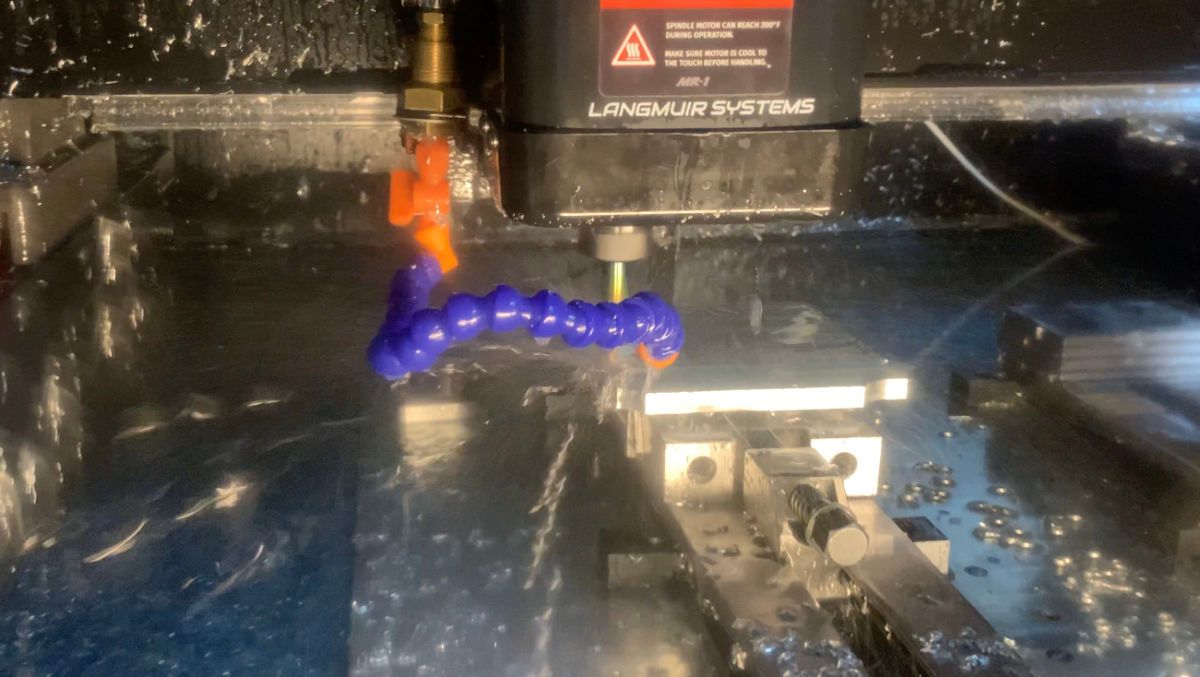

Figure 8: Progressive Images of the bulk material removal operation on the backside of the fidget spinner body.

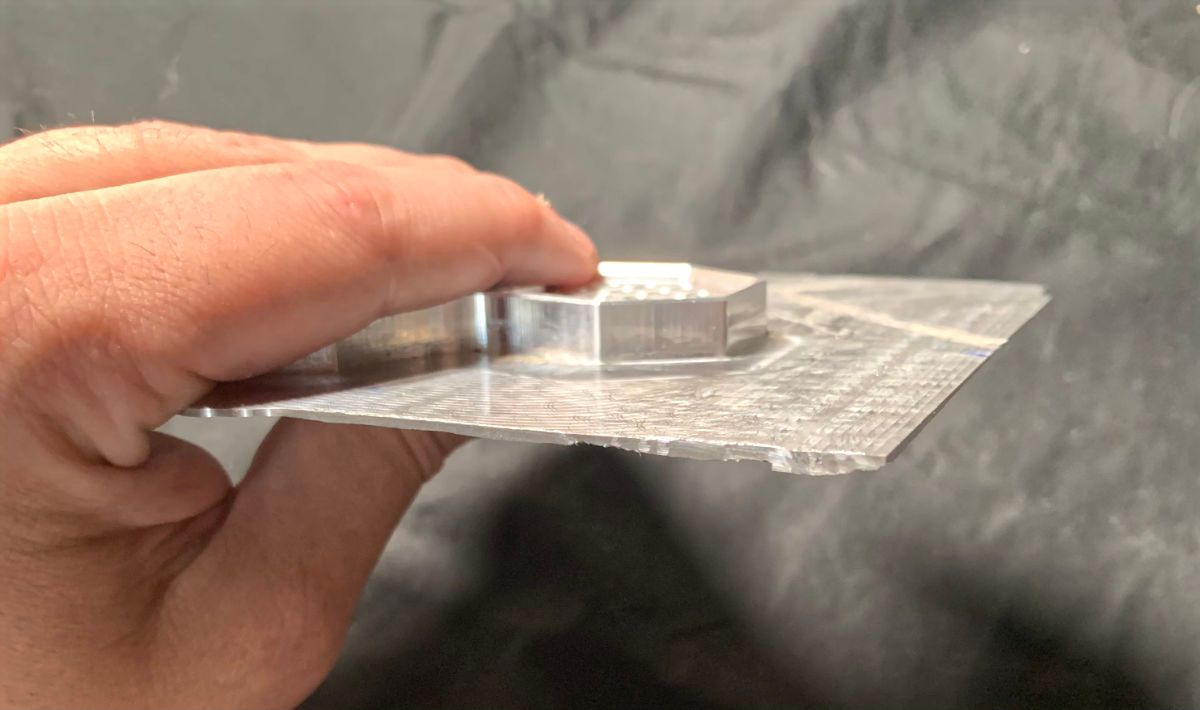

I was nervious but hopeful that the cutter would remove the remaining material. I watched on the edge of my seat, promising myself I would change the tool path if I were to make this part again when BAM! The part was pulled out of the vise about a half millimeter and I immediately smashed the emergency stop button. I was too stubborn to scrap the part and try again with a different tool path... and now something had definitely gone very wrong. Figure 9 compares the thickness with the cantilever distance. Of course the fully unsuported 1.5mm thick part 2.25" away from the vise was vibrating!

Figure 9: Comparison of overhang distance from vise support and material thickness.

When I was generating the CAM program, I had paused with some concern about this exact problem, but ironically decided that it would be better for the tool life if the amount of engagement was kept lower. This is normally a very reasonable thought... unless going with a lower tool engagement causes vibration and chatter.

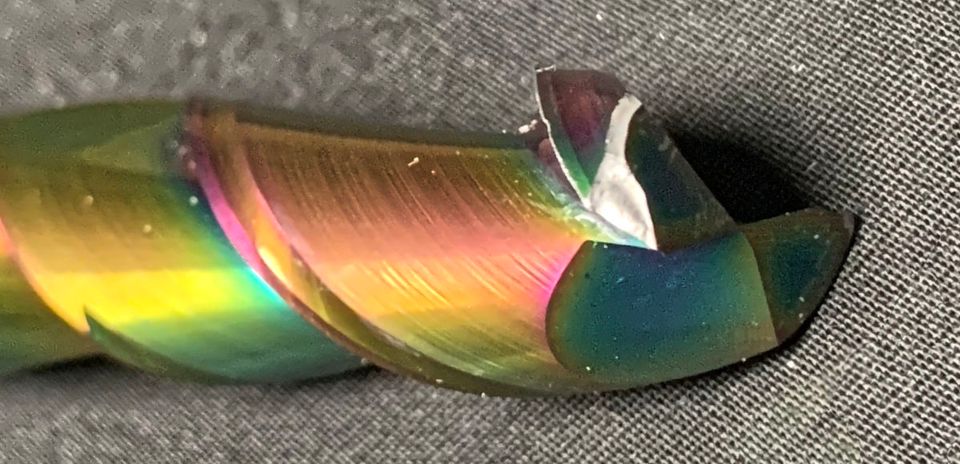

After removing the tool from the spindle and inspecting it, the vibration had been so great that one of the cutting tips of the tool had broken off. Thankfully, the part was of low consequence and while the tool isn't exactly cheap, things could have been much worse.

I've ordered a new end mill and made peace with my mistake. I also now know to never use tool paths like this ever again.

Maybe next weekend I can actually make a fidget spinner.