What is force?

Prerequisites Required: None

Today, we are going to talk about force.

Nope. Wrong kind of force. Instead, we are interested in physicists' and engineers' definition of force.

The motivation for defining force comes from causality, the idea that events build upon each other in a cascade that causes objects to evolve. For a process to be causal, one event leads to the next which leads to the next, and so on. A fundamental expectation of our universe is that the properties of objects are casual. For example:

- A paper is blank until a person writing on it with a pencil causes markings to appear on it.

- A steak is raw until it is caused to be cooked by being placed onto a fire.

- An object sits on the table until it is caused to be moved onto the floor by a cat.

This last example is of high relevance.

We make the following unprovable yet apparently obvious statement about the nature of the universe:

The position of objects is causal.

This fundamental observation was packaged by Isaac Newton in his First Law of Motion:

"Every body must persist in its state of rest or of moving uniformly in a straight direction, except in so far as it is forced to change that state by impressed forces."- Isaac Newton (translated from native latin)

This should be intuitive. If objects are not moving (at rest), they remain not moving and some cause is required to get them moving. By the same logic, if an object is moving at constant speed, it remains moving at constant speed and some cause is required to bring it to a stop.

To bring a moving object to a stop is to change the objects speed, so any sort of change in speed also requires a cause.

Newton referred to any cause that changes the velocity of an object a force.

Whenever the speed of an object changes, it is accelerating. Therefore, any object's acceleration is caused by a force.

Consider the below experiment where a person pulls a block and a spring.

The hand pulls on the spring, which transmits the force to the block, which causes it to accelerate. There is something else we should keeny observe from this experiement. Due to the force applied by the hand, the spring deforms!

Forces cause objects to accelerate and deform.

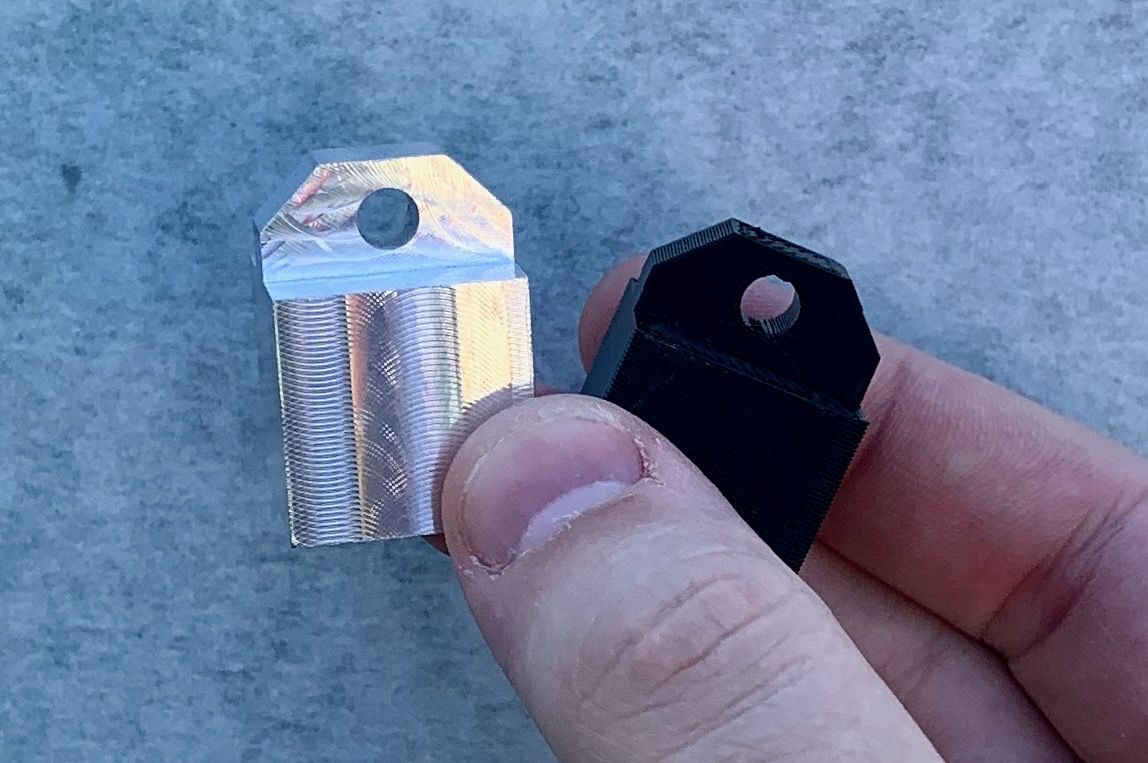

Consider we do the experiment again, but with a machined aluminum block rather than a 3D printed plastic one.

During the experiment where the accelerations of the mass are similar, we make two observations:

- We had to exert more effort with our hand when pulling the aluminum block.

- The spring deformed greater pulling the aluminum block.

We conclude that the force required to accelerate this metal block is greater than the plastic block. Even though the blocks were the same size.

We also observe that if I throw these two blocks of identical size, one block takes more effort, more force for me to throw. (Unfortunately, a video of me throwing these blocks wouldn't really demonstrate the effort I felt, I challenge you to try it for yourself).

This difference in effort to throw the blocks is due to differences in their mass, the resistance of objects to acceleration. We define it as:

$$ m = \frac{F}{a} $$

where $m$ is the mass, $F$ is the force, and $a$ is the acceleration. There is a subtlety here that I want to make clear. We discovered mass by observing the effort required to accelerate objects of different materials. We measure mass by comparing the effort required to accelerate objects of different materials.

After hundreds of years of detailed experimentation, we have found that mass is a very stable property. Measure mass today and tomorrow and you get the same answer. Cut an object of uniform material and measure the mass of each piece and you get $\frac{1}{2}$ the mass of the full object. Physicists have experimentally verified the consistency mass so many times that they have called it a fundamental law of the universe.

"In any closed system, the mass of the system must remain constant over time. Mass cannot be created or destroyed."- The Law of Conservation of Mass

The definition of mass can be inverted to obtain the most common equation in physics, Newton's 2nd Law of Motion:

$$ F = ma\: [Newton's\:2nd\:Law] $$

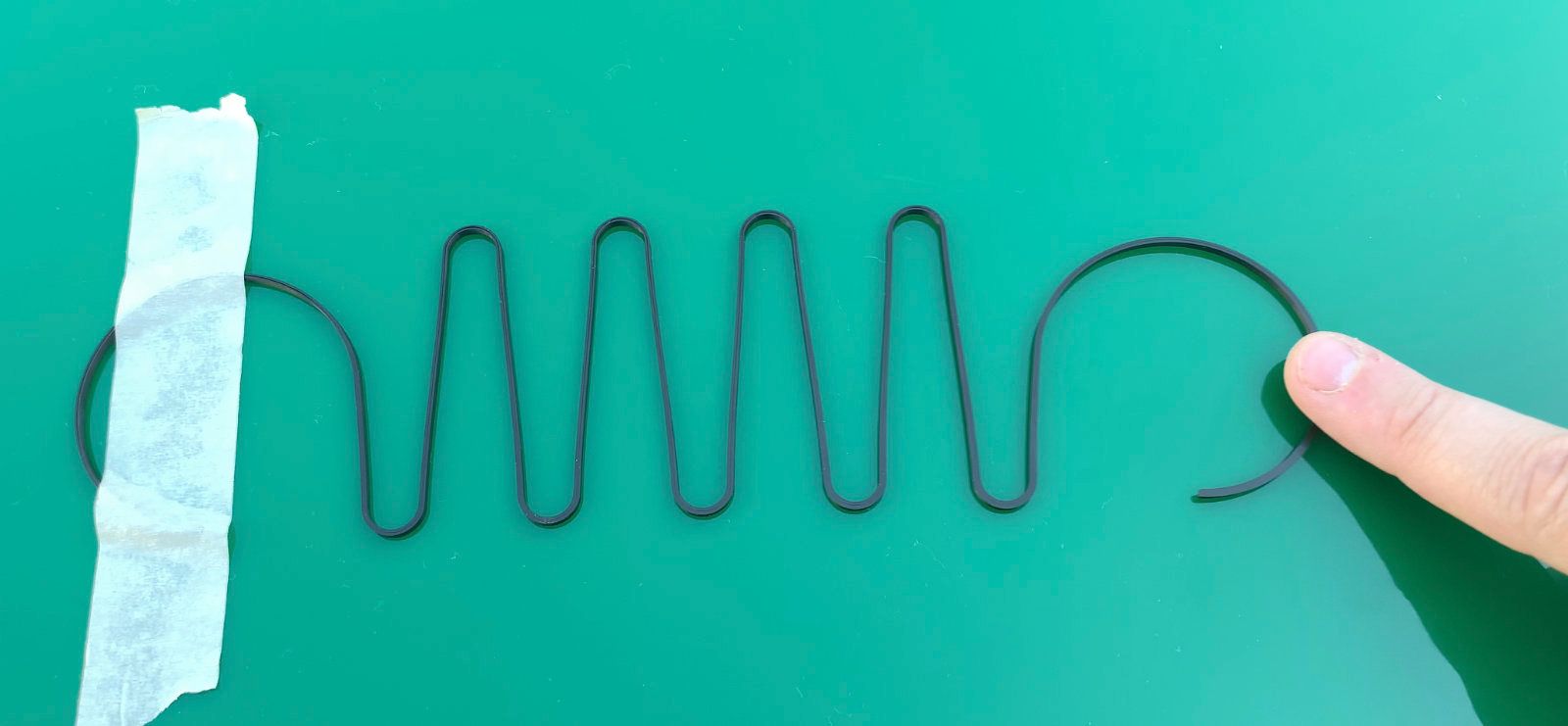

Recall that forces can cause both acceleration and deformation. If we take a spring, tape it to a board, and apply a force with our hand, the spring stretches and continues to transmit force between the tape and the finger, even in the absense of acceleration.

Figure 5: Spring taped to a uniform color backer board.

This example demonstrates Newton's 3rd Law of Motion.

"For every force, there is an equal and opposite force"- Newton's Third Law of Motion

The finger pulls on the spring, which pulls back on the finger.

The right end of the spring pulls on the left end of the spring, which pulls back on the right end.

The left end of the spring pulls onto the tape which pulls back on the left end of the spring.

This cascades on through every single object involved in the interaction, down to the ground all the way through to the person's muscles. It can be easy to become overwhelmed; typically we simplify the situation by making simplifying assumptions.

We might assume the tape is a rigid constraint on the end of the spring and that the finger is a pure force generator. These assumptions make any other objects in the force transmission chain unimportant (assuming they are good assumptions).

Reference Frames and Fictitious Forces

There is a certain reality to experimentation that requires a scientist to have both a device to be experimented on and a device observing the experiment, an observer and observee.

Consider the below clip depicting a train:

Which of the following situations is occurring in the clip:

- The camera is riding on a golf cart accelerating toward the right of the train.

- The train is accelerating toward the camera's left.

- The train is accelerating toward the camera's left AND the camera is riding on a golf cart accelerating toward the right of the train.

Have an answer yet? All answers provide a fairly convincing explanation for the motion in the camera, however, if one is to determine the cause of the motion and assign forces, it's critical to understand which situtation is occuring.

In situation 1, the force is applied to the camera while in situation 2, the force is applied to the train. In situation 3, forces are applied to both the camera and the train!

In all situations, the train appears to be accelerating to the left of the camera, and without additional information, the experiment would conclude that a force is being applied to the train to cause it to accelerate, even if it's actually the camera that is accelerating and the train isn't moving at all!

The dual nature that observing changes in motion requires both an object and an observer fundamentally broke early physicists. How can you tell which is which? It's hard!

To avoid this confusion, physicists declared a proper observer must not be accelerating. They called these "non-accelerating" observers inertial reference frames. If the observer is not accelerating, then all forces are on the objects being observed, not the observer, and we know that all the forces are real.

How do you determine whether your observer is an inertial reference frame? Simple. You must account for the cause of every acceleration or deformation (from rest) on an object being observed and that cause must be actually acting on that object.

Consider the following example. Sitting in a car, you let go of a ball and it flies toward the back seat. Is there a force being applied to the ball causing it to accelerate backward?

No. An observation from a camera on the ground outside the car (a more proper inertial reference frame) would reveal that the car is accelerating so that when you let go of the ball, the car's seats accelerate toward it.

When we are uncertain whether a force is real or fictitious, another means of determing whether a force is real is to look at deformations of objects in the force transmission chain.

In the top frame of the below experiment, the camera is simply moving left and right (fictitious force) while in the bottom frame, deflection of the spring makes it obvious that a real force is indeed being applied to it.

Deformation is actually the most reliable indicator of whether a real force is applied. Unfortunately, most objects are quite rigid so it is difficult to use this indicator in many real life examples. We can often set up special experiments to deduce the true nature of certain forces from experimenting on deformable bodies.