What is gravity?

Prerequisites Required: Basic Understanding of Forces

Gravity is the most familiar cause for acceleration in the human experience. Drop a ball and it falls to the ground. Isaac Newton observed this tendency for objects to accelerate toward the ground and built a physics empire that transformed the world.

Is gravity a force?

When considering the cause of gravity, there are two possible options for describing gravity, stemming from the dual nature of observer/observee (read this article for more on this dual nature):

-

An invisible and non-contact force called gravity acts between two objects (like the earth and a ball) and causes them to accelerate towards each other.

- Dropped falling objects are pulled by the force of gravity which causes them to accelerate toward the ground.

- Stationary observers on the earth's surface continue to be pulled by the force of gravity but the surface provides an equal and opposite force. Stationary observers are therefore not accelerating and are inertial reference frames.

-

The fabric of space and time itself is distorted so that objects appear to accelerate to the earth (similar to a ball moving backward in an accelerating car).

- Dropped falling objects appear to be accelerating toward the earth because the earth's surface accelerates toward the objects. Dropped objects are therefore not accelerating and are inertial reference frames.

- Stationary observers on the earth's surface have a force applied to them by the surface of the earth; they are being accelerated upward by the surface of the earth.

Isaac Newton felt that option 1 seemed far more likely than option 2; clearly the notion of distorting space and time itself is ridiculous, these are just imaginary coordinates we use to describe the relative positions of objects and duration of events in our universe. In the next few experiments, we will prove him wrong.

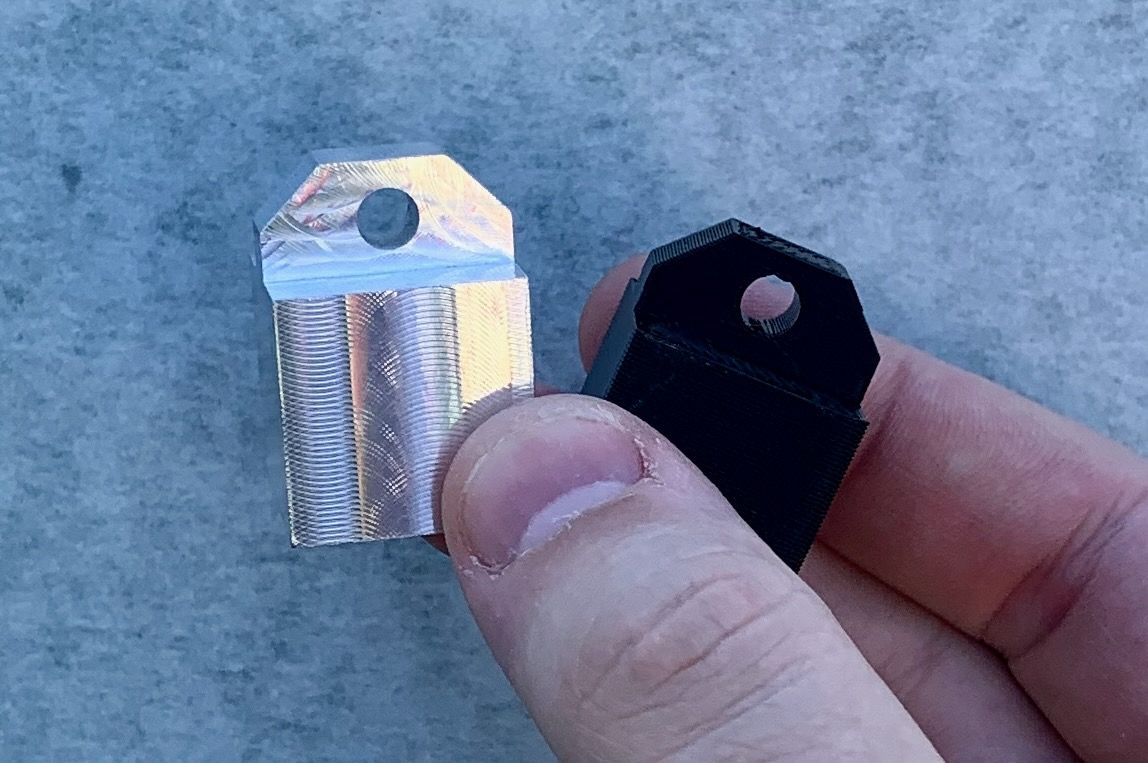

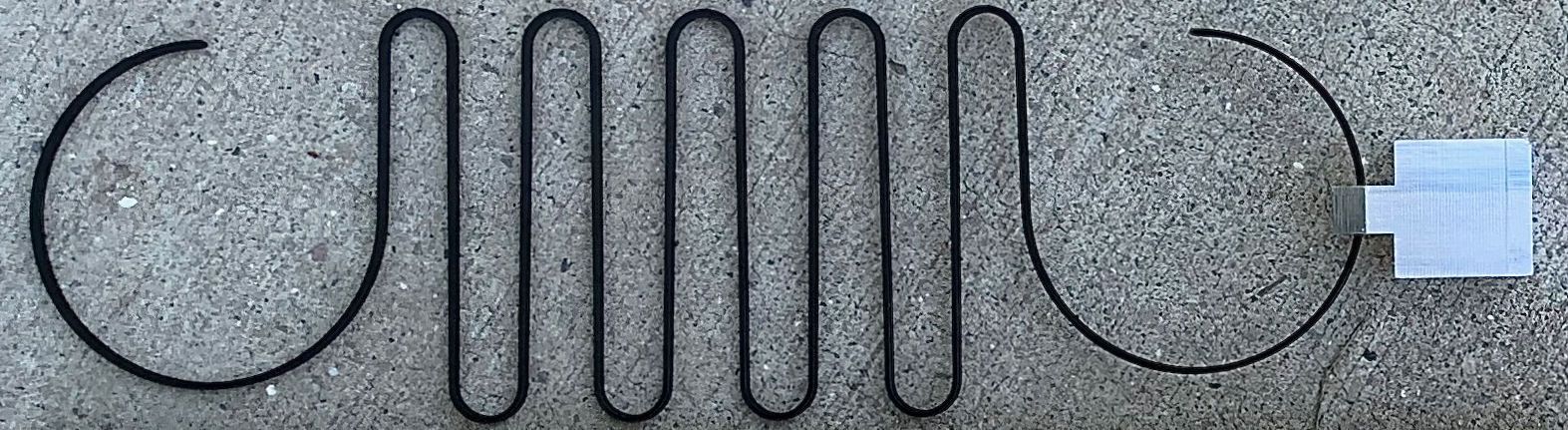

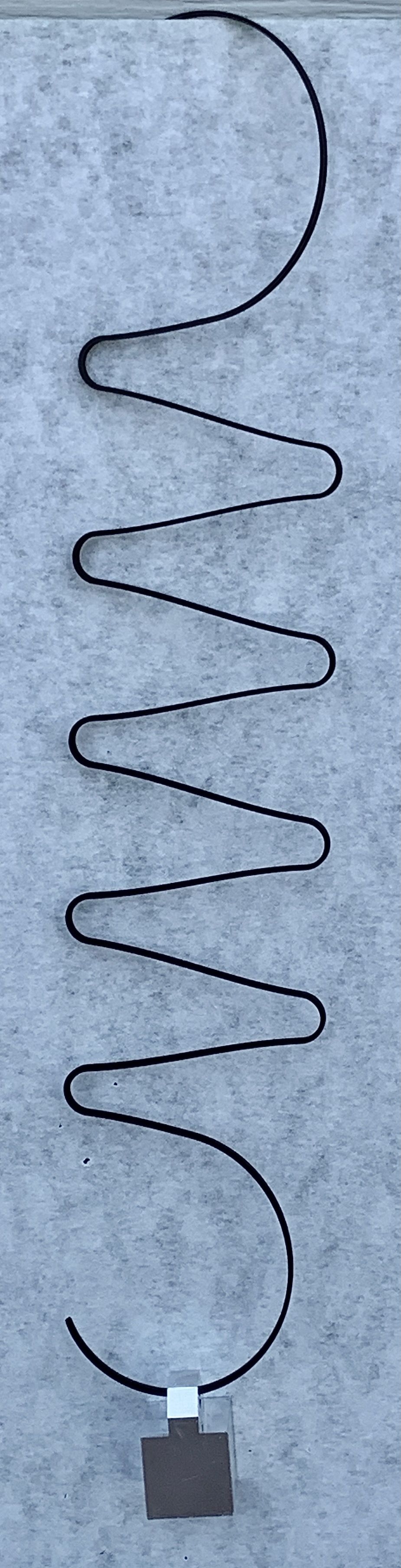

Consider the below experiment. We've got a couple of weights (aluminum and PLA) and a light spring.

- We measure the length of the spring (194mm long unstretched).

- We measure the lengh of the spring with both the aluminum and PLA blocks secured to the end (220mm).

Figure 1: Measurement of spring and weights.

We observe that when the spring is sitting on the ground in a horizontal orientation, the spring remains unstretched. When a force is applied to the spring by a hand, it deforms and moves.

We conclude that the spring sitting unmoving is inertial in the horizontal direction; there are no changes in deformation.

We also conclude that the spring being pulled by the hand is non-inertial in the horizontal direction; there are changes in deformation.

From this preparatory experiment, we make the following statements to test the nature of gravity:

- When the object is stationary on the earth's surface:

- If it is undeformed, it is inertial. (Agrees with description 1 of gravity)

- If it is deformed, it is non-inertial. (Agrees with description 2 of gravity)

- When the object is dropped:

- If it is undeformed, it is inertial. (Agrees with description 2 of gravity)

- If it is deformed, it is non-inertial. (Agrees with description 1 of gravity)

Experiment 1: Hang weight and observe deformation

Figure 4: Hanging weights in experiement 1.

Frame 1 of the experiment is simply to demonstrate that I am in fact letting the weight hang under the influence of gravity. Frames 2 and 3 demonstrate the outcome. The objects are unmoving yet a deformation is present. This suggests that objects hanging stationary on the surface of the earth are non-inertial.

Experiment 2: Drop a weight and observe deformation

Figure 5: Falling weights in experiment 2.

By inspection, we can see that during the dropping, the objects are moving yet no deformation is present. How strange! The lack of any deformation would suggest that the the accelerating object is actually inertial.

Both experiments 1 and 2 agree on the same conclusion; description 2 of gravity is correct. An object falling toward the surface of the earth does not experience a force due to this acceleration. Instead, us, the observer are being accelerated upward by the surface of earth which makes static objects appear to be falling.

Objects appear to accelerate to the earth relative to surface observers. It is the observers who are being pushed by the surface of the earth and accelerate upward.

During his famous thought experiment comparing a man jumping off a building to a man floating in space, Albert Einstein came to the same conclusion. After years of development, in 1915, Albert Einstein published in great detail the mathematical foundation to model this behavior in his General Theory of Relativity.

"This is absurd! If the ground were accelerating upward, wouldn't the earth be expanding!"- You, right now.

It is understandable if this conclusion breaks your mind. We would intuit that sitting stationary on earth should be an inertial frame because we don't observe any acceleration. What we don't typically get to observe is the deformation of these objects that demonstrates they are not in an inertial frame.

The mathematics of general relativity are deep. In order to explain this behavior, Einstein posited that gravity causes distances and time itself to contort to create the appearance of gravity. For me, one very helpful representation comes from Alessandro Roussel (ScienceClic):

Additional materials on general relativity are available at the bottom of this article if you are so interested.

Is gravity a force?

No, it is not. It is a ficticious force generated by the upward acceleration of the ground together with contracting spacetime that causes objects to appear to accelerate downward.

We experience our entire lives in a non-inertial frame, constantly accelerating upward. Even laying on the ground, unmoving, the earth's surface accelerates our bodies upward through contracting spacetime. This makes it very challenging to intuit what an inertial frame really is.

Objects above the ground are not experiencing any force but due to contracting spacetime they accelerate toward the ground.

Gravity is Uniform

We've now established that gravitation is the apparent acceleration of objects toward the ground. One question of interest is whether all objects are affected equally by gravity.

Because gravity is actually caused by the distortion of spacetime and the upward acceleration of the stationary ground observer, we would expect that all objects should "fall" equally under gravity uniformly.

Gravity uniformity is very easily demonstrated to be true by dropping or throwing two different objects. They approach the ground with identical acceleration and hit the ground at the same time.

Figure 6: Throwing weights to compare their acceleration.

Geographic variations of the earth mean that the observed acceleration is not constant, typically varying between about $9.78 \frac{m}{s^2}$ and $9.83 \frac{m}{s^2}$.

The 1901 General Conference on Weights and Measures (an international organization that defines global standards for measurements and constants) defined the standard earth gravitational acceleration to be:

$$ g_s = 9.80665 \frac{m}{s^2} $$

Due to the varying actual gravitational acceleration, it is customary to use a simpler value:

$$ g = 9.8 \frac{m}{s^2} $$

Note that this value is accurate to within about $\pm 0.3 \%$ of any local gravitational value and to be more precise, you would really need to measure the local gravitational acceleration yourself.

Simplified Gravity

The mathematics that encompass general relativity's description of gravity are complex.

As mechatronics engineers who typically build things near the surface of the earth (more than 99.9999% of stuff is built intending to be used near the surface of the earth) we make huge simplifying assumptions of general relativity.

We ignore the complicated distortion of time and space from general relativity. Time is absolute. Space is absolute.

We assume that gravity is a uniform acceleration that causes objects to accelerate toward the earth.

Newton's second law, $F = ma$ allows us to equate accelerations to forces (even if they are actually fictitious).

We fabricate a fictitious force, gravity, and claim the following:

- The force of gravity is equal to the mass of the object multiplied by the acceleration due to gravity: $F_g = mg$

- The acceleration from gravity acts uniformly and equally on all objects.

- The reason objects do not deform in mid-fall is because uniform gravity applies the same force everywhere in an object. For an object to deform, equal and opposite forces must be applied to it.

This simplifying assumption actually works REALLY well to describe most situations we will encounter. We call this description of gravity simplified gravity.

There are a few situtations in which this description of gravity breaks down:

- Attempting to describe the mechanics of large bodies' gravitational influences on each other. Planets, stars, and black holes are obviously beyond the scope of our constant uniform acceleration simplification.

Additional Background on Newton's Universal Law of Gravitation

We've done nothing yet to justify observations about gravity beyond the surface of the earth. Issac Newton combined observations about gravity on the earth with observations of celestial bodies to make a bold conclusion:

Gravity is a force between two objects, dependent on their masses and distance.

He formulated an equation to describe this force, which he called the Universal Law of Gravitation:

$$F = G\frac{m_1m_2}{r^2}$$

$F$ is the force due to gravity acting to pull the two objects closer, $m_1$ and $m_2$ are their mass, and $r$ is the distance between the centers of the two objects. $G$ is the universal gravitational constant:

$$G = 6.6743 \times 10^{-11} \frac{Nm^2}{kg^2}$$

Newton used this law to predict and observe the motions of celestial bodies to good success (it was the failures of this law to correctly predict certain motions of celestial bodies and light that encouraged physicists to seek out general relativity).

Consider an object near earth:

- The earth has a large and constant mass.

- The earth has a very large radius; an object falling near the surface of the earth does not significantly change the distance between the centers of of the earth and object.

Under these assumptions, we find the force is constant:

$$ F = m_1(\underbrace{\frac{Gm_{earth}}{r_{earth}^2}}_{g}) $$

$$ F \approx m_1 g $$

Let $r = 6378137\:m$, $m_{earth} = 5.9722 \times 10^{24}\:kg$ (you can imagine that it is very difficult to estimate the radius and mass of the earth, these are published by NASA at Earth Fact Sheet.

Substituting these values and assumptions into Newton's Law of Universal Gravitation, we find that

$$g \approx 9.8 \frac{m}{s^2}$$

This matches our simplified description of gravity.

2. Attempts to describe the behaviors of light with simplified gravity fail spectacularly.

3. Simplified gravity fails to describe accelerometers.

Accelerometers

The goal of this article isn't to teach about accelerometers, but the primary reason I introduced you to general relativity (albeit in its simplist form) is becuase if you do not understand the true nature of gravity, accelerometers will completely break your mind (as they broke mine).

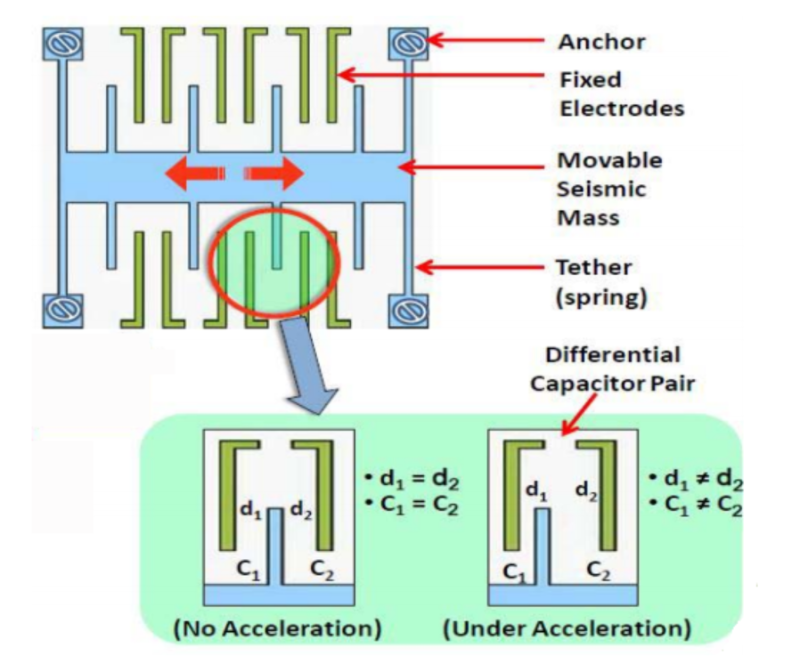

Accelerometers are devices that claim to measure acceleration. The output of an accelerometer is in units of acceleration, typically in $\frac{m}{s^2}$ or in terms of earth's gravity, $g's$.

Even though accelerometers output units of acceleration, they don't directly measure the acceleration some observer might measure. Instead, the deflection of a spring between the outer body of the accelerometer and a mass is measured. This deflection is caused by force applied to the accelerometer.

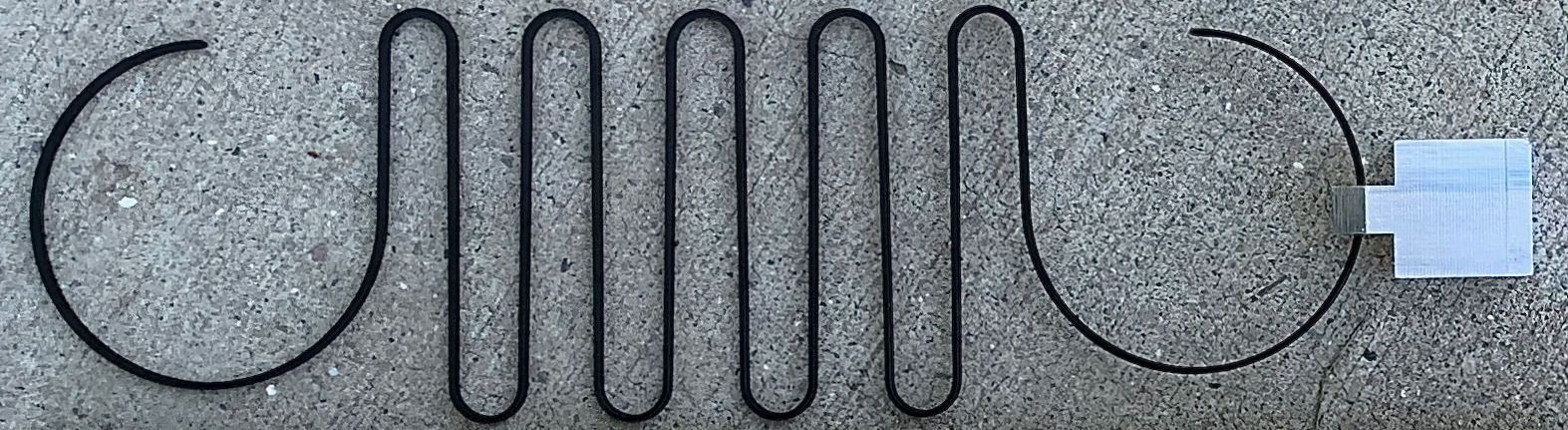

The spring/mass device we built earlier to study the effects of gravity is actually a type of accelerometer. Commerical accelerometers are typically better packaged but measure forces in a similar manner.

The below figure describes a microscopic accelerometer, commonly called a MEMS (Micro-electromechanical system) accelerometer.

As we saw earlier, an accelerometer laying horizontally and falling looks the same.

When an accelerometer is free falling to the ground under the influence of gravity, it will not read any acceleration.

Also as we saw earlier, an accelerometer sitting on the ground is caused to deform due to the upward force of the surface of the earth.

When an accelerometer is sitting on the ground at rest, it will read $+1g$ of acceleration.

Warning: You may encounter situations where accelerometer vendors attempt to obfuscate this nature. They may flip the signs of all axis (they sometimes call this the 'gravity vector'). They may attempt remove the average in order to make the accelerometer read zero when sitting on a table (this can yield really chatoic results when the accelerometer is rotated). These tricks are sometimes useful, but be certain to be aware when they are being used.

Some accelerometers have properties that cause them not to be sensitive to static and low frequency accelerations (like gravity). These accelerometers would not measure any acceleration while sitting on a table, but they also wouldn't measure acceleration while falling or while a steady acceleration is applied (like in an accelerating car).

Additional sources for General Relativity

To be frank, general relativity is not a subject I work with regularly. Products I build operate a speeds far less than the speed of light and the simplified model of gravity is good enough for most terrestrial machinery.

Alessandro Roussel, (ScienceClic) and Dr. Derek Muller (Veritasium) are both wonderful individuals who try to provide clear explanations for challenging concepts in physics. They are far from the only sources but their discussions are very approachable and serve as a jumping off point to learning more about general relativity. I have linked to a few of their videos below.